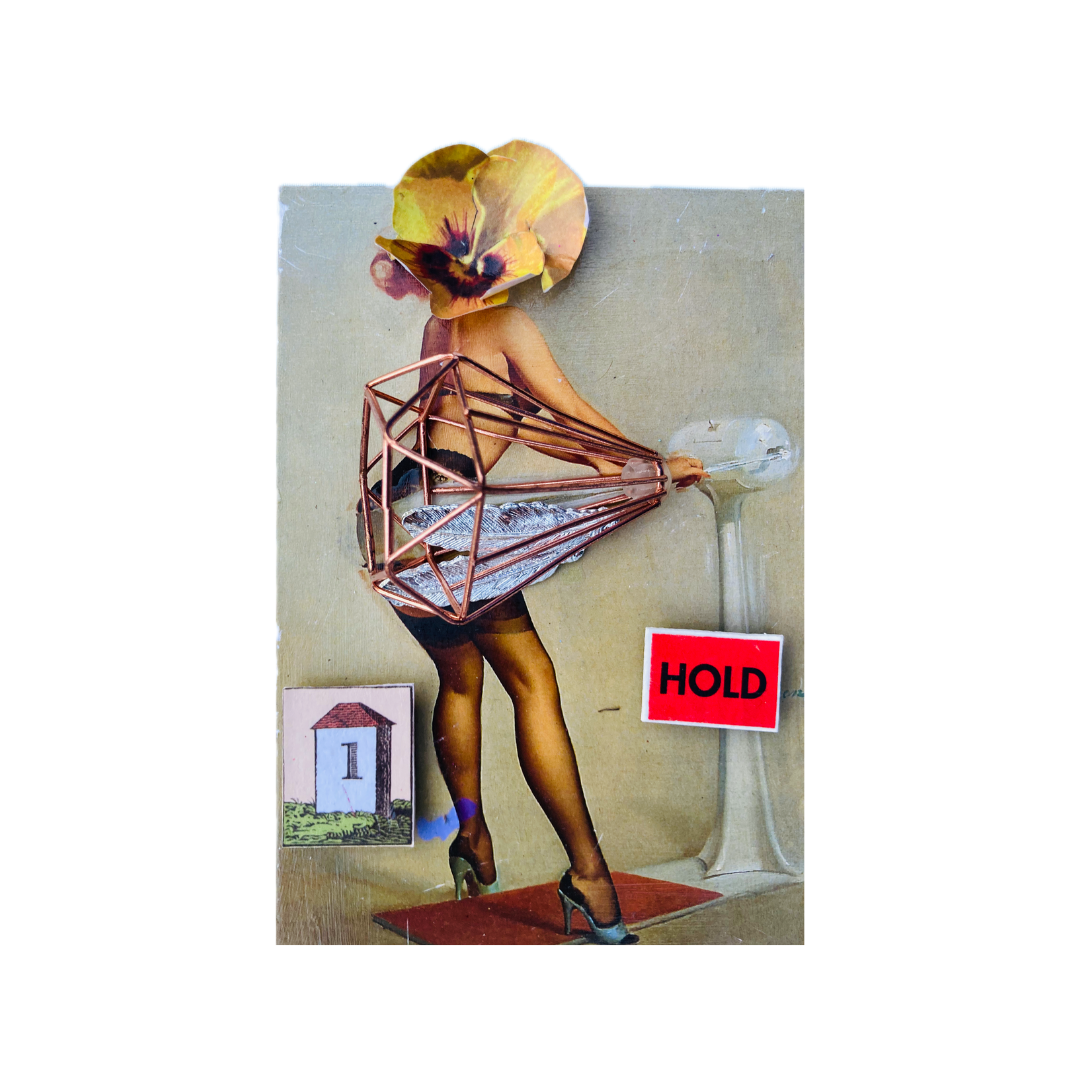

Here we encounter the perfect ideological short-circuit of late capitalism: the pin-up girl, that supposedly innocent fantasy object of male desire, literally overlaid with the bureaucratic detritus of global trade—shipping manifests, container codes, customs declarations. But this is not simply a matter of "critique" in the banal sense of exposing how women are "commodified." No! The true perversity lies elsewhere. What we witness in these works is the obscene underside of the capitalist fantasy itself. The pin-up girl has always-already been a commodity, yes, but she functions as what Lacan would call the objet petit a—the object-cause of desire that sustains the entire libidinal economy of consumption. She is not simply sold; she sells the very idea that desire can be satisfied through purchase. But here comes the genius of the gesture: by literally papering over these images with shipping documents, we see how the global supply chain—those anonymous containers crossing oceans like unconscious thoughts—constitutes the true pornography of our time. The real obscenity is not the exposed female body, but the exposed logic of circulation itself: goods, bodies, desires, all reduced to tracking numbers and bill-of-lading codes. The container, that perfect architectural metaphor for repression, reveals its contents only at the moment of unpacking. Similarly, these works perform a kind of ideological unpacking—they show us that the eroticized female form and the mundane logistics of global trade are not opposites but the same phenomenon viewed from different angles. The pin-up promises satisfaction while the shipping manifest delivers it, both operating through the same fundamental logic of fetishistic disavowal: "I know very well that this woman/commodity cannot fulfill my desire, but nevertheless..." In the gap between the promise of the image and the reality of the shipping note, we glimpse the true coordinates of contemporary subjectivity: always in transit, always deferred, always tracked but never quite arriving at its destination. The female body becomes the perfect empty container for our displaced anxieties about global capital—simultaneously hypervisible and utterly instrumentalized. This is why these works are not simply "feminist" in the predictable sense. They reveal instead how the very gesture of critique can become complicit with what it opposes. We look at the pin-up covered in shipping codes and think we have learned something about "objectification," but perhaps we have only learned to eroticize our own critical distance from the problem. The true question is not: how do we liberate the female body from commodification? But rather: how do we confront the fact that our very desire to liberate has itself become a commodity, another item in the global circulation of progressive posturing?

—With proper Hegelian ruthlessness, these works force us to enjoy our symptom.